Ecosystem ecology:

Pools and fluxes

So far this semester

- Dynamics of individual populations

- Keep track of individual organisms’ birth rate & mortality rate

- Dynamics of species interactions

- Keep track of overall types of interactions, e.g. competitive, consumer–resource

- Species diversity over space and time

- Patterns over large and small scales

Now

- Ecology of ecosystems

- How are abiotic properties distributed on Earth, what shapes their distributions, and how they affect life on Earth.

Core themes from the Syllabus

Ecological systems are dynamic, meaning that their properties can change over time.

Ecological systems feature feedbacks, meaning that the dynamics of one component of a system often affects another.

The dynamics and wellbeing of ecological systems are tightly intertwined with the dynamics and wellbeing of human societies

Understanding ecological systems requires us to confront uncertainty, which can arise because of limited knowledge of the system, or due to inherently stochastic processes.

Scope of ecosystem ecology

Patterns and drivers of major energy/substance fluxes

Over this week, we will consider the global drivers of nitrogen and water

We will frequently talk in terms of “pools” and “fluxes”

Today’s case study: how precipitation shapes ecological patterns, and vice-versa.

https://neo.gsfc.nasa.gov/view.php?datasetId=MOD17A3H_Y_NPP

Net primary productivity across the globe

- NPP = Carbon stored by photosynthesis - carbon lost during respiration

Some questions that an ecosystem ecologist might study

What determines the productivity of a system, and why is it so different across the globe?

How does productivity relate to biodiversity?

How might ecosystem productivity be affected by human activities?

What determines the productivity of a system, and why is it so different across the globe?

First-order explanation: productivity is shaped by precipitation and temperature

The question then becomes, what shapes precipitation and temperature?

- Structural explanation

- Dynamic explanation

Structural factors behind temperature

- Spherical shape -> Latitudinal gradient in temperature

- Tilted axis -> Seasonal variation in temperature

Structural factors behind temperature

- Why are tropics warm and poles cold?

A first-order explanation

- Angle of incidence varies – perpendicular at equator, not so at the poles

- Energy travels through more atmosphere before reaching earth at the poles than at the tropics

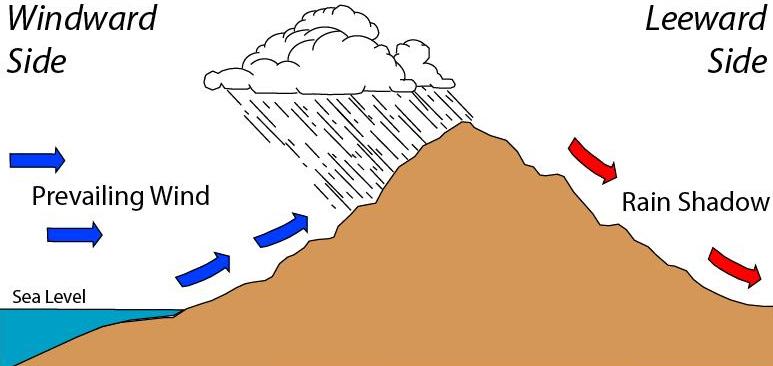

Structural factors behind precipitation

- Why are tropics rainy, and deserts tend to be away from the tropics?

A first-order explanation

Structural factors behind precipitation

- Why is there variation within the tropics, with some areas drier than others?

Rain shadow effect

This leads to a simplistic conclusion

- Tropical areas are wetter due to wind patterns

- Rise of mountains creates rain shadows

- Productive tropical forests dominate in lowland areas of the tropics.

But…

Patterns of precipitation are not driven by “structural” factors alone

- Consider the impacts of trees on precipitation

- How much water does an “average” oak tree transpire annually?

Patterns of precipitation are not driven by “structural” factors alone

Landscapes with vegetation that transpire more water will have larger evapotranspirative flux, which moves water from the groundwater pool to the atmospheric pool

Depending on what happens to the atmospheric water, this can cause more rainfall

Human modified landscapes often have reduced rates of evapotranspiration

(fig. 2 from Spracklen et al. 2018, Annual Reviews of Environment and Resources)

Large reductions in rainfall expected due to land-use change

(fig. 2 from Spracklen et al. 2018, Annual Reviews of Environment and Resources)

Changes in rainfall can lead to “regime shifts”

A more subtle story of the water cycle in the Amazon basin

This analysis provides compelling observational evidence that rainforest transpiration during the late dry season plays a central role in initiating the dry-to-wet season transition over the southern Amazon

The fate of the southern Amazon rainforest depends on the length of the dry season.

The length of the dry season also depends on the rainforest.

Feedbacks at the ecosystem scale

Cloud seeding as a way to “trigger” more rain?

Why does this matter?

- Large-scale ecosystem processes are not just ‘set in stone’

- They are always in relationship with the biological processes that unfold

- This means that disruptions to the biology can have important consequences to the ecosystem as a whole

Ecosystem Ecology, continued

Pop “quiz”

(Don’t worry, you’re not graded on this)

If it takes 1 million seconds for something to happen, how long is this in days?

If it takes 1 billion seconds for something to happen, how long is this in days?

How about a trillion?

Review from previous lecture

- Primary goal of ecosystem ecology is to study the relationship between abiotic and biotic components of Earth

- e.g. What determines the distribution of various abiotic properties (e.g. temperature, precipitation) and how does this shape life

- And vice-versa – how does life on Earth affect abiotic cycles?

- Ecosystem ecology prioritizes understanding pools and fluxes

- Ecosystem ecologists deal with big numbers!

- Humans don’t usually have a great intuitive feel for these. So try to convert into units you do know.

Pools and fluxes vary in their sizes – by many orders of magnitude!

- These pools and fluxes are not set-in-stone

- Living organisms (including humans) can have drastic impacts on pools and fluxes

- e.g. through a back-of-envelope calculation, we guesstimated ~4 million gallons (~16 million liters) of water are transpired by oaks on LSU’s campus

- What portion of the global transpiration flux does this represent?

- Changes to fluxes can change the distribution of life on Earth

- E.g. reduction in tree density –> reduction in transpiration –> reduction in local precipitation?

Let’s dive into the Nitrogen cycle

(Note that the absolute mass of atmospheric \(N_2\) is \(3.9 \text{e} 10^{18} \text{ kg}\))

Why is Nitrogen a critical component of life on Earth?

Simpler version of the N-cycle

Goal for today: identify the major fluxes of N-cycling and their drivers

Nitrogen cycling

- A vast majority of Nitrogen is in the atmosphere, but is unusable for biological activity (\(N\equiv N\))

- \(N\) enters the biological realm through nitrogen fixation (\(N_2 \to NH_3/NH_4^+\))

- Nitrogen fixation driven by soil bacteria (diazotroph)

- Transformation of N within the biosphere (\(NH_3/NH_4^+ \to NO_3^-/NO_2^-\))

- N leaves the biological realm through denitrification (\(NO_3^-/NO_2^- \to N_2\))

- Let’s go through the major fluxes

Nitrogen fixation

- An important avenue through which inert \(N_2\) becomes bio-available

- N-fixation is a series of biochemical processes that are energetically expensive, and only carried out by a small group of bacteria (diazotroph)

- Rhizobacteria, Frankia, many cyanobacteria (e.g. Anabaena)

- These bacteria associate with specific plants (legumes, alders, Azolla)

- Biological N fixation accounts for ~ 140*10^9 kilograms of N fixation annually

- For reference, the atmosphere holds 3.9*10^18 kilograms of N

\[N_2 \to NH_3 \text{ or } NH_4^+\]

What happens to N after it is “fixed”?

Some of the \(NH_3\) and \(NH_4\) in soil can be directly consumed (‘assimiliated’) by plants

But a substantial portion is processed by nitrifying bacteria, which oxidize ammonium into nitrites or nitrates (\(NO_2^-\) or \(NO_3^-\))

What happens to N that is fixed?

- One potential outcome: it is taken up by plants

- In some cases, the microbes in fact have a direct exchange with plants.

- Legume-Rhizobia interactoins: A classic example of mutualisms

What happens to N in ammonium or nitrates?

- One potential outcome: it is taken up by plants (assimilation)

- Assimilation can also happen through direct uptake of soil N by plant roots

- And it can also be mediated by fungal partners (“mycorrhiza”)

What happens to N that is assimilated?

- N used to build new plant tissue (e.g. leaves, seeds, fruits)

- This N can be shed (litterfall, or ‘detritus’)

- Or this N can be consumed by herbivores

- Eventually, N consumed by herbivores can be consumed by higher consumers

- All such N will turn into detritus

What happens to N in the form of detritus?

- N in detritus is present in the form of biomolecules (e.g. in DNA, in proteins, and so forth)

- This N cannot be taken up by plants

- Needs to be further converted back into bio-available N

- Detritivores begin the process of converting detritus

- and Decomposers complete the biochemistry to mineralize Nitrogen into bio-available \(NH_3\)

What happens to N converted by decomposers?

Potential to be re-assimilated by plants

Some portion of nitrates (\(NO_3^-\)) get reduced by denitrifying bacteria, back into \(N_2\)

Lost back to the atmosphere.

Main fluxes in the N cycle

- N-fixation from atmospheric \(N_2\) into ammonium

- Nitrification of ammonium into nitrates

- Consumption of ammonium and/or nitrates by plants (assimilation)

- Return of N in the form of detritus

- Decomposition of detritus back into bio-available N

- Denitrification of nitrates into \(N_2\)

Going back to one of the overarching questions of ecosystem ecology:

- What regulates the magnitude of these fluxes?

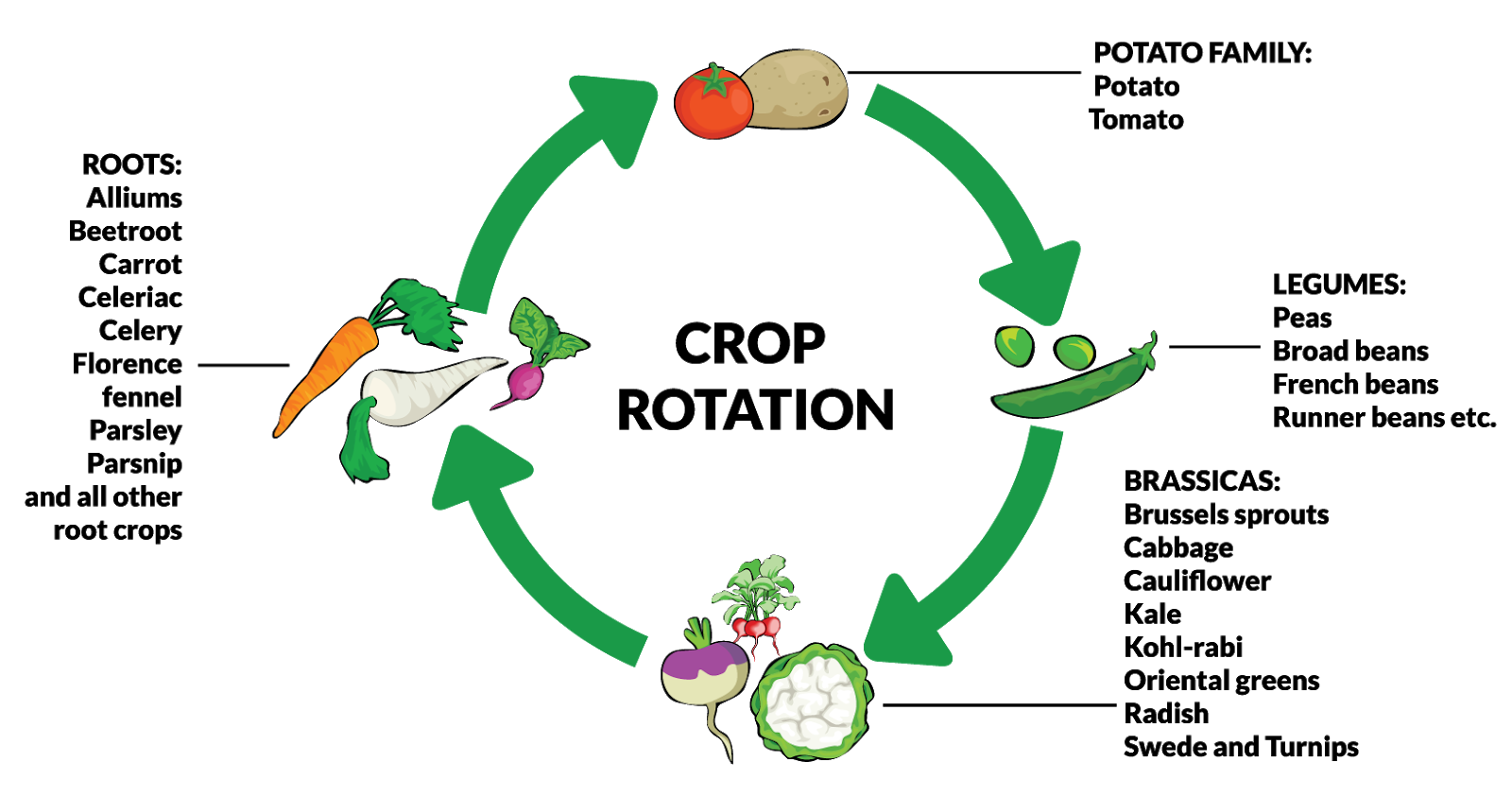

Rate of Nitrogen fixation

- Largely determined by the composition of the soil bacterial community

- Which in turn depends strongly on the plants in the system

- Plant communities dominated by legumes tend to have higher rates of N-fixation

- Crop rotation practices reflect this

Rate of Nitrification

- Determined largely by the composition of the soil bacterial community

- Fairly restricted group of bacteria able to do this

- Also affected by presence of oxygen in the soil

- Water-logged soils have lower levels of available oxygen

- Lower rates of nitrification

Rate of Nitrogen assimilation

- Diversity of plant community and remaining trophic network

- Other abiotic conditions - levels of other nutrients, water, temperature, etc. also control rate of biological activity

Rate of decomposition

- Makeup of the detritus

- Generally, detritus with higher levels of \(N:C\) (nitrogen-rich) decompose more quickly than with lower levels of \(N:C\)

- (But substantial variation in this pattern)

- Also determined by the composition of the soil detritivore and decomposer community

- Detritivores largely comprise invertebrate and vergebrate animals that physically break down detritus

- Decomposers largely comprise of micro-organisms (fungi and bacteria) that convert N into different forms

Rate of denitrification

- Abundance of denitrifying bacteria

- Environmental conditions (anoxic conditions –> higher rates of denitrification)

The nitrogen cycle

- The \(N\) cycle is very much driven by how differently different organisms use N.

- Although there’s a lot of \(N\) on Earth, much of it is not biologically available

- Given that N’s use is so different across organisms, feedbacks between the abiotic and biotic components of the ecosystem are critical.

- Preview for Friday: Given the importance of N for life, it is often a limiting nutrients. Humans have done a lot to affect this (e.g. crop rotation as mentioned), and some human interventions have had drastic effects.

How humans have pushed and pulled the nitrogen cycle

Major pools and fluxes

Pools: Atmosphere; Soils; Living things (in our DNA, proteins, etc.); water

Fluxes: Biological fixation (by bacteria); Nitrification (by bacteria); Assimilation (by plants); Consumption (by animals); Decomposition (by bacteria and fungi); Denitrification (by bacteria)

- Also, N-fixation by lightening

But this is not the complete cycle

Almost as much N-fixation happens through “Industrial processes” as through Biological N-fixation

- How?

- Industrial applications and implications

Coupling of terrestrial and aquatic N cycle

- Human activity has substantially increased the flux of N into biologically-active forms

- This leads to much more ‘rapid’ movement of Nitrogen through ecosystems

- Rather than cycling within the soil, substantial amounts of N run off from land into nearby aquatic systems

How would this affect aquatic systems?

What happens when terrestrial and aquatic N cycles are coupled?

- Eutrophication

- High levels of nutrients, especially including N and P, run from land (e.g. farms) into lakes, streams, rivers, and ultimately, oceans

- Pulse of nutrients into these aquatic systems changes the ecological dynamics

What happens when terrestrial and aquatic N cycles are coupled?

- High nutrients lead to rapid rates of growth of algae

- Exponential growth because carrying capacities are eliminated

- High levels of surface-level algae suppresses light levels lower in the water body

- Harms other aquatic plants

- Lowers levels of dissolved oxygen in water

- Leads to ecological ‘dead zones’